Poland and Hungary are moving fast towards a new state-led model of development that could heighten tensions with foreign investors and the European Commission.

Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania were never closer to fullling economic criteria for the adoption of euro, however, most of them have never been farther from making this commitment.

Their governments have resigned on setting yet another half-hearted deadline for adoption as voters only gradually re-warm to single currency with the average public support lingering at about 42%. All these countries are legally committed to adopt euro once they fulfill formal prerequisites, but rely on the “Swedish loophole” in the Treaty that gives them full control over the timing of the entry. While eurozone reforms, Brexit and long-term developments keep changing the political and economic calculus of the case for euro, the adoption remains fundamentally a political decision.

Life in the Second EU Lane

The Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker has recently upped the ante on the eurozone enlargement by stressing that the “euro is meant to be the single currency of the European Union as a whole.” There were even unofficial leaks—subsequently denied—that the Commission was considering a 2025 deadline for euro adoption. These discussions are clearly related to Brexit as the group of euro non-members is about to lose the only political heavyweight. This is likely to shift the dynamics of the economic negotia- tions in Brussels and, consequently, the non-eurozone countries will have to expend a lot more political capital to secure exceptions from EU laws increas- ingly tailored to the purposes of the single currency.

Such a power shift will come on top of other political cleavages that weaken the position of the non-euro countries in East Central Europe. The restraints on basic democratic principles in Poland and Hungary had already triggered calls for changes in the EU funding programs. There is a possibility of access to EU subsidies being tied to compliance with EU commitments, reforms, and anti-graft rules in the post-2020 budget. The Commission has also proposed to re-channel some structural funds exclusively to those committed to euro adoption via a separate technical assistance and cash-for-reform program fostering the convergence during the run-up to the single currency.

Moreover, when one more member—such as Bulgaria—joins in, the eurozone members will gain a so-called reinforced qualified majority in the Council of the European Union. This is one of the peculiarities of the Lisbon treaty, which allows the Council to circumvent the Commission in passing EU laws. It would allow the eurozone to drive hard bargain as the non-members lose the cover of the Commission that tends to safeguard and balance interests of all EU members.

There were even unofficial leaks—subsequently denied—that the Commission was considering a 2025 deadline for euro adoption.

However, it is not only the prospect of a two-speed EU that is changing the political calculus on euro adoption. There is a positive economic attraction as well. Currently, the eurozone is growing faster than the US and is no longer as fragile as a decade ago. While further reforms of the eurozone are necessary, the introduction of the European Stability Mechanism, overhaul of the Stability and Growth Pact, the creation of the banking union, and the crisis-response policies of the European Central Bank improved the future resilience of the single currency. This is especially relevant for smaller economies that cannot overwhelm the current capacity of the new crisis management mechanisms and, therefore, are well insured against the worst consequences of any future banking or economic crisis.

No Uniform Response

Recently, the response of non-euro countries to evolving eurozone circumstances became more diverse. Bulgaria has announced its intention to enter the European exchange rate mechanism (ERM II), which is likely to lead to euro adoption 2 years later.

Moreover, when one more member—such as Bulgaria—joins in, the eurozone members will gain a so-called reinforced quali ed majority in the Council of the European Union.

To regain stability after several crises, Bulgarians tied their currency to Euro in 1997, which is akin to having all the disadvantages of the single currency without many of its advantages. Hence, the recent decision is not particularly surprising and follows the Baltic countries that had similar currency arrangement. Croatia is also keen to join in soon due to high degree of “euroization” of its economy, where the single currency is widely used by corporates as well as households that would all benefit from the prompt removal of the currency risk. However, the government in Zagreb has struggled to meet the deficit and debt criteria during the last decade and needs to consolidate the economy before setting any timetable.

The remaining four countries lack a comparable justification for immediate adoption, which gives prominence to more general debate on the desirability of euro. The single currency was construed in 1992 for a subset of then 12 countries that could fulfill the Maastricht criteria. The differences in their levels of economic development were much smaller than in the current EU of 28, so economic convergence was not a central issue. Yet, it is becoming one in Czechia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania, either out of genuine concern or simply as the last stand for Euroskeptic arguments, when formal criteria are met.

Euro in Good Times and Bad Times

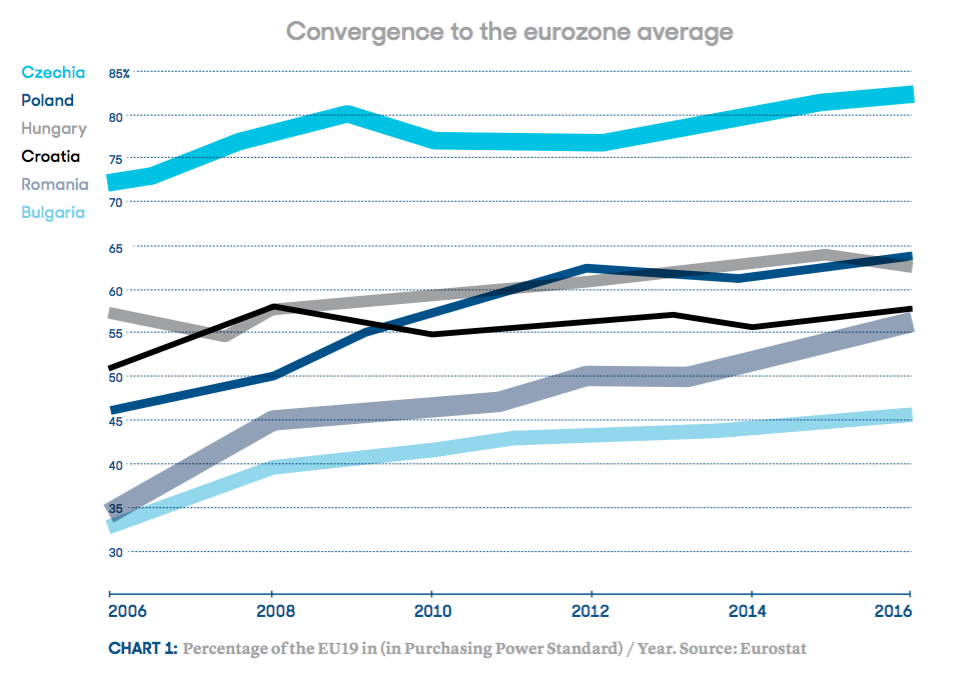

The economic convergence is not a necessary pre-requisite for a successful currency union. After all, Mississippi is at 53% of economic development of Massachusetts, Lincolnshire at 66% of Cheshire and Olomouc at 38% of Prague, while they share the same currency. Hence, for Bulgaria—at 40% of Germany—joining the eurozone would not be extraordinary (Figure 1). However, it is the dynamic of economic convergence—especially in good and bad times—that matters for the sustainability of the currency union.

In the good scenario, the economic growth in poorer countries would be consistently higher allowing for quick convergence. Such growth spurts tend to be triggered by currency devaluation that starts an export-led boom which is sustained by continuous improvements in productivity. Growth spurts also lead to rapid increases in wages and asset prices that increase inflation. However, higher inflation quickly makes exports more expensive, unless compensated by a decrease in the value of domestic currency. Yet, the single currency precludes depreciation, thus suppressing the growth spurt before it gets started as higher domestic prices immediately translate to the loss of export competitiveness.

Croatia is also keen to join in soon due to high degree of “euroization” of its economy, where the single currency is widely used by corporates as well as households.

This is a serious argument against the euro adoption as long as one predicts a growth spurt in foreseeable future. Alas, most Central European economies have already exhausted the convergence bene ts of the export boom based on low wages and undervalued currencies over the last two decades. The next growth spurt would have to be based on innovations that improve productivity in non-eurozone more rapidly than in eurozone. However, these countries generally lack the physical and human infrastructure for rapid innovation. Hence, keeping the national currency in the hope for growth spurt seems overly optimistic. It is more likely that the convergence will proceed gradually over long periods of time, which does not create differences in inflation that would have to be compensated by the exchange rate. Gradual convergence is fully compatible with the single currency that provides stability, access to a large market, transparency of prices and low transaction costs of trading.

The bad scenario is based on the recent experience of the Southern economies, where the single currency deepened and prolonged economic slump. The eurozone was designed in early 1990s, when the belief in the disciplining and self-stabilizing powers of financial markets was at its peak. This had helped to dismiss arguments of central bankers that the single currency needed crisis-management mechanisms, because it seemed inconceivable that sophisticated markets in advanced economies could ever nance massive real estate bubbles and profligate governments for long enough to re-create the 1930s-like crisis.

The crisis struck the euro and non-euro economies alike, which attests that the fundamental cause was not single currency but the failure of financial markets to understand risks. However, the non-euro economies had two advantages: first, as international bankers remained at least somewhat sensitive to exchange rate and political risks, the destabilizing financial inflows were relatively smaller, and, second, they could use the depreciation of their currencies to restart export-led growth. This allowed economies at the Eastern end of the EU to grow out of crisis a bit quicker and with relatively less wage-cutting and austerity than was the case for some eurozone’s Southern members.

However, national currency is a shock-absorption mechanism which Eastern economies use reluctantly. Latvia or Bulgaria chose deeper aus- terity rather than giving up on their fixed exchange rate. Czechia, Hungary, Poland, and even Romania maintained relatively stable exchange rates to euro during the decade before and after the crisis. They experienced sharper fluctuations only in 2008 and 2009, when they rode through the largest financial storm in 80 years. This contrast with Southern economies that relied on frequent devaluations in response to much less extreme economic challenges, as, for example, Italy devalued 13 times during the two decades prior to euro adoption.

In the good scenario, the economic growth in poorer countries would be consistently higher allowing for quick convergence.

The economic history provides ample warnings that financial crises are not a thing of a past. However, the really big crises that would make Eastern economies rely on the flexible exchange rate are rare and the next one may come in several decades. Maintaining a small independent currency for that long can prove a risky luxury as in another economic circumstance, small currency can become a curse; it is prone to speculative attacks, vulnerable to domestic political risks, and generally requires higher interest rates. The cumulative costs over time can easily outweigh any bene ts in the next crisis.

Meanwhile, the eurozone is much less likely to experience a re-run of the crisis. The preventive measures were strengthened and crisis management tools added to its institutional architecture. Equally important were changes in the financial market regulation. Although, these are not directly related to the single currency, they should prevent repetition of excessive lending that made eurozone vulnerable.

The bad scenario is based on the recent experience of the Southern economies, where the single currency deepened and prolonged economic slump.

Financial regulators are now equipped with macro-prudential tools that can compensate for the fact that the single monetary policy of the ECB cannot be optimal for all eurozone economies. The banking union cut the “doom-loop” between governments and banks, which made even macro-economically sound governments like Spain or Ireland insolvent when they were forced to save big private banks. Last but not least, the EU also launched the capital markets union project that should increase the role of non-banking nance that can absorb crises without state aid. Given enough time, sustained reforms and continued integration of European economies can bring the eurozone closer to the optimal currency area ideal so they can reap the bene ts of euro while also jointly containing its risks.

Euro Adoption Is Politics after All

The decision to adopt euro is inevitably political. Not in the sense of the usual criticism of the single currency as a political project, but in terms of voters’ support. While economic theory can predict the consequences of euro under various scenarios, it cannot predict with any degree of certainty which scenario is going to materialize in the decades to come.

The preventive measures were strengthened and crisis management tools added to its institutional architecture. Equally important were changes in the financial market regulation.

Since economics cannot help voters to decide, they have to rely on their own outlook of the future. The single currency will be an acceptable proposition for voters whose views are compatible with international collaboration. Even among them, the perennial optimists believing in a rapid convergence are going to push for postponing euro adoption by a decade or more. Given the achieved level of convergence, such delay makes much more sense in Romania than in Czechia (Figure 1). Similarly, the pessimists believing that another massive financial crisis is not decades but years away, can plausibly argue against euro adoption in order to preserve the shock-absorption capacity.

However, it is the middle-class voters whose living standards are converging to the Western levels, who are the most likely supporters. If this group continues to expand and maintains hopes for the future of gradual improvements, the support for euro adoption will be increasing. Moreover, unpredictable events, such as country-specific banking or currency crises can also reveal the costs of maintaining a small national currency and sway public opinion. Furthermore, sustained growth of living standards in neighboring euro countries would also serve as important reminder that gradual convergence works better within the single currency than outside of it. After all, nothing would be more eye opening than the reversal of centuries-old labor flows, when Czechs or Hungarians start seeking jobs in Slovakia or Poles in the Baltic states.