The winners and losers of the current variant of globalization are pitted against one another, just as in the past. Although the losers are becoming politically radicalized, forecasts concerning the demographic development for the near future nevertheless raise the hope that, even in the era of hyper-globalization, the negotiating power of human labor will continue to grow. This is why we must continue to adhere to the principles of the freest world trade possible, and not succumb to dark analogies with the twentieth century.

The one whose name must not be spoken. A terrifying figure. This is how central bankers and the world’s leading economists came to see U.S. President Donald Trump soon after he was elected in 2016.

The fact that they regard the U.S. President as their Lord Voldemort became apparent as early as last year, at the elite Jackson Hole symposium in Wyoming. All the bankers and economists attending the conference seemed to be under his spell.

In global terms, the share of the economically active population has increased enormously, when compared to economically dependent children as well as economically dependent seniors.

Although Mario Draghi, President of the European Central Bank, did not explicitly mention Trump in his address, it was nevertheless obvious that he was making a plea for continued globalization and free trade precisely because the current White House occupant was the anti-globalizing Lord Voldemort.

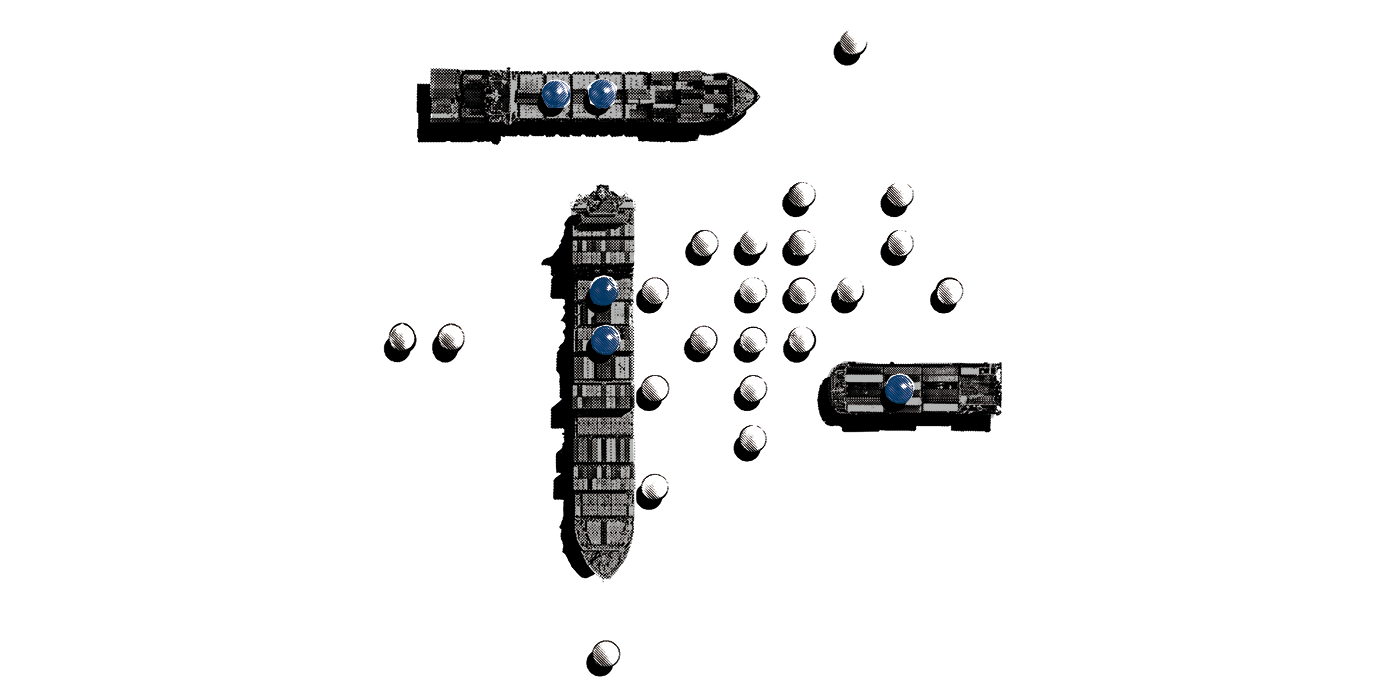

Draghi also explicitly cited Dani Rodrik, a Harvard economist who has drawn a parallel between the first wave of globalization, which occurred roughly between 1870 and 1914, and the current wave of globalization, or – to use Rodrik’s term – hyper-globalization. The first wave was linked to inventions such as the railroad, the steamboat or the telegraph. It had its winners and losers.

Rodrik argues that in their frustration the losers eventually resorted either to left-wing radicalism in the form of Communism, or to national radicalism in the form of Nazism or Fascism. This resulted in the emergence of totalitarianism, which left much of the twentieth century steeped in blood. In Rodrik’s view, the political radicalization that accompanies the current hyper-globalization is as alarming as it is predictable, due to historical experience and the laws of economics.

Rodrik thus believes that it was equally predictable that the losers – for example, a factory worker in Detroit who has lost his job to a Chinese laborer working for a bowl of rice – would be driven by a Pavlovian reflex to leap into the comforting arms of some radicalizing political trend of a nationalist or left-wing nature, just as in the twentieth century.

The nationalist trend is epitomized by Lord Voldemort Trump or France’s Marine Le Pen. Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn in Britain, as well as movements such as the Greek Syriza or the Spanish Podemos, represent in contrast the left-wing trend.

Re-living the horrors of the twentieth century

Political polarization is undoubtedly underway in the West, with growing inequality in the era of globalization being a key cause. This is why Draghi and Rodrik have called for “modified globalization”, which would ensure a continuing increase in redistribution that would, in turn, alleviate symptoms of inequality.

Rodrik’s chilling analogy with the developments of the first half of the twentieth century is, unfortunately, not entirely surreal. It is quite likely, however, that re-living the horrors of the twentieth century might – rather surprisingly – be fended off by the process of demographic ageing not just in the West but also in countries such as China.

On first hearing, this may sound rather bizarre since, after all, ageing is a key threat faced by the world. So how could it possibly be the blessing that might fend off Rodrik’s glum parallel?

The global economy has been in a rather extraordinary situation for some 35 years. In global terms, the share of the economically active population has increased enormously, when compared to economically dependent children as well as economically dependent seniors. This has occurred because, while birth rates have been decreasing, the increasing life expectancy at birth, a key factor in population ageing, has yet to manifest itself to an extent that might stem the growth of the share of the economically active in the overall population.

This share has culminated in the current decade and is set to decrease, most noticeably in the economically developed part of the planet. It has released an enormous global supply of labor, following a boost in the late twentieth century, when the relatively isolated countries of Central and Eastern Europe and China, in particular, joined the global market.

Human labor is less precious and valuable

Over a short space of time, these countries’ participation brought about an unprecedented increase in the labor force, of a dizzying 120 per cent, which the global market was able to tap into. In the era of hyper-globalization, this is a major reason for the stagnation of wages that has particularly affected the developed economies of the West. For a while, it has simply made human labor less precious and valuable.

The West, and China in particular, are facing decades of palpable ageing. The ratio of economically active individuals to older people will decrease dramatically. This is likely to lead to tax rises.

The UN predicts, however, that by 2040 the annual growth in the world’s population will slow from the current 1.25 per cent to 0.75 per cent. The West, and China in particular, are facing decades of palpable ageing. The ratio of economically active individuals to older people will decrease dramatically. This is likely to lead to tax rises, necessitated by the increasingly urgent need to increase old age pensions, while the pressure on wage rises will also continue to grow.

This is because human labor will become scarcer and thus also more expensive, despite the increase in automation and robotization. The negotiating power of employees will grow considerably, purely for economic reasons, without any need to strengthen the role of trade unions. The diminishing proportion of wages in the total size of the economy, as recorded in developed countries since the 1970s, is thus likely to reverse of its own accord quite soon. This, in turn, will destroy the key source of inequality and thus also of political polarization, raising the hope that Rodrik’s analogy may be wrong.

Although the full scope of the horrors of the twentieth century might not materialize, political polarization today is quite evident. It is embodied in the figure of Donald Trump, with his steps to impose import duties being its symbolic manifestation. Trump hopes that tariffs will put an end to the unfavorable effects of hyper-globalization. He believes that by making Chinese labor more expensive he will restore jobs in Detroit.

Trump is behaving like a typical estate agent

In this respect Trump is behaving less like Lord Voldemort than like a typical estate agent. He is betting on the use of power. This is what his experience has taught him: it’s either me or the competitor who will own this lucrative building in Lower Manhattan or that great property in Florida. There is no other option, no compromise is possible. Similarly, Trump tends to view foreign trade as a zero-sum game. He must suspect that the trade war he has unleashed this year might also affect the U.S. economy, but he is betting that it will impact China or the European Union sooner and to a greater extent.

Trump tends to view foreign trade as a zero-sum game. He must suspect that the trade war he has unleashed this year might also affect the U.S. economy.

At first sight, his bet seems to be working out. Current U.S. growth figures have exceeded expectations. Over the course of the third quarter of this year, the economy has grown by 3.5 instead of the predicted 3.3 per cent. This growth has been driven primarily by household consumption.

Growth has also been significantly boosted, however, by companies stocking up on goods and filling their storehouses to the rafters, driven by fear of an escalating trade war. Trump has threatened to impose further tariffs on Chinese imports as early as next January. It would be foolish to bet on an early end to the trade war with China. This is why U.S. firms are hoarding. But of course, you cannot keep hoarding forever. It is a one-off effect that will begin to wear off in the current, fourth quarter. And what will be left behind is fear. Fear of the impact of the trade war. It must be quite enormous if it can shake up macroeconomic figures to such a degree. Otherwise, U.S. firms would not be quite so eager to hoard.

As long as companies fear an escalating trade war and further tariffs, they will be filling their storehouses, creating a beneficial effect in the short term. In the run-up to the midterm elections, Trump took credit for this. The same fear, however, is making companies hesitant to invest. The rate of investment in the third quarter was sluggish. This could augur the start of an economic slowdown in the U.S. and before too long the painful impact will also be felt elsewhere, including in Central and Eastern Europe and within it, the Czech Republic.

Open economies are highly sensitive to cost increases

It is precisely the small, open economies such as the Czech Republic’s that are deeply enmeshed in global value chains, making them highly sensitive to any cost increases in international trade. Larger EU economies, Germany’s in particular, are also entangled in these chains to a higher degree than is the U.S. This does indisputably put Trump at an advantage which, in turn, amplifies – albeit indirectly – the negative impact on the Czech Republic, whose main business partner is the EU in general and Germany in particular. Trump thus indirectly represents the greatest threat to the Czech Republic’s economic prosperity. Should he impose fresh tariffs, for example, on car imports from the European Union – an idea he continues to toy with –the negative impact on the Czech Republic would be felt mainly by subcontractors of German car manufacturers rather than by companies exporting finished cars, since the Czech Republic’s annual exports of these to the U.S. amount to merely a few dozen.

The question is whether the outcome of the November elections to the U.S. Congress will deter Trump from imposing fresh tariffs. Although the American President declared the results of the elections “a tremendous success”, he must undoubtedly also see it as a kind of warning for the 2020 election that is approaching slowly but inexorably.

The fact that the Republicans failed to translate the low unemployment and (as of early November) a still rather strong stock market into a better election result should thus serve as a stark warning to Trump.

On the other hand, Trump is the fourth President in a row to lose his majority in the House of Representatives two years after being elected, suggesting that such a result may be the rule rather than the exception. Admittedly, Trump has been aided by an exceptionally well-performing economy, whereas his predecessor Barack Obama was not so fortunate. The fact that the Republicans failed to translate the low unemployment and (as of early November) a still rather strong stock market into a better election result should thus serve as a stark warning to Trump, given that this election was, to a large extent, a referendum on his performance in the White House to date.

The tense atmosphere in global trade

Although the Democrats have gained control over the House of Representatives, it is far from certain that this will put an end to the trade war. A divided Congress is likely to reach consensus not only on further infrastructure expenditures but also on a continuation of the trade war with China. The Democrats are historically more inclined to impose new, higher tariffs than the Republicans, and thus they – or at least many of them – might back Trump’s policy towards China.

The question remains whether Trump himself will continue to escalate the issue. It is also possible that in light of the election result, even without actual pressure from the Democrats, the President will tone down the rhetoric of his own accord and start behaving less aggressively, and not only in terms of the trade war.

The Democrats are historically more inclined to impose new, higher tariffs than the Republicans, and thus they – or at least many of them – might back Trump’s policy towards China.

But should that fail to happen, the Czech economy should brace itself for significantly slower GDP growth and higher unemployment. The tense atmosphere in global trade overall has already begun to make the Czech economy less dynamic. The growth figures for the third quarter have been quite disappointing, unlike those for the other three Visegrad Group countries, where growth exceeded expectations. The Czech economy has apparently suffered the consequences of being linked too tightly to the German car industry, which in the third quarter was indeed hit by the effects of the trade war.

The stakes are high

Should a trade war of moderate gravity and lasting longer than several quarters or even years become a reality, economic growth in the Czech Republic would slow, on average, by 0.9 to 1.2 percentage points. By adopting an appropriate economic policy, the Czech economy could subsequently adjust to the new conditions. In the worst-case scenario, however, it could slump into prolonged economic stagnation that would inflict even more marked longterm societal damage on the country and its population. In summary, the stakes are high. As long as the mentality of a real estate agent and the idea that world trade is a zero-sum game prevails in the White House, we will be the losers. And this is true not just of the smaller and more open economies, but will eventually also apply to everyone else.

Demographic ageing and the related increased scarcity of human labor and the growing negotiating power of employees might in the future provide a strong counter-current to social polarization and radicalization. Until then, however, everything possible needs to be done to ensure that the perception of global trade does not suffer irreversible damage. It is imperative in this respect to staunchly defend the principles of the freest global trade possible because its benefits will become much more apparent again in the future, in every walk of life.

We invite alumni of the Aspen Young Leader Program to present their projects, thoughts and inspiration in Aspen Review. Aspn.me/AYLP