Lviv, with its population of about 750,000 people, is only the seventh-largest city in Ukraine. In the western part of the country, however, it is the largest one, at least three times bigger than any other city in the region. This endows Lviv informally with a certain metropolitan status—as the cultural, educational and, to a certain degree, economic and political center of “Western Ukraine”.

On 4 April, shortly after the first round of Ukraine’s presidential elections, the Vice News website found a peculiar way to celebrate that event by attaching a photograph of camouflaged youngsters to the very title of a report that read: “White Nationalists from around the World Are Meeting in Finland”. There was no reference to Ukraine in the article but the text for the photograph fixed the omission. It implied that the most exemplary “white nationalists from around the world” would in all probability be “[m]embers of the right-wing National Corps [who] are marching toward the election campaign rally of Petro Poroshenko, President of Ukraine and candidate for the 2019 elections, in Lviv, Ukraine, Thursday, 28 March 2019”.1

It is not the featuring of a Ukrainian far-right group that makes the material so peculiar (although this kind of coverage is highly inflated in the international media and too often follows the Kremlin template). The key-words in the text are “Poroshenko” and “Lviv”,—both of them tightly connected, according to the same template, to the notion of “Ukrainian nationalism”,—whatever it means and however the usage is justified. The only problem, in this case, was that the camouflaged people in the photograph were not marching to the Poroshenko rally to support him, as the text implied, but to obstruct and disrupt it. This was a systemic campaign carried out not only in Lviv,2 but also in Vinnytsia,3 Ivano-Frankivsk,4 Cherkasy,5 Chernihiv,6 Poltava,7 Zhytomyr8 and all around the country.9

In all other regions beyond the west, any use of Ukrainian in public was stigmatized as a sign of rural backwardness or, worse, a defiant manifestation of “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism”.

There was a great deal of information on this, also in English,10 so that any responsible author or editor could easily verify it and discover the real role of the far-right in Poroshenko’s campaign. Vice News failed to do this—despite definitely not belonging to the Kremlin pool of propagandistic outlets. They simply internalized common wisdom disseminated by Moscow, and this for so long and so intensively that it has been established, becoming a kind of proven fact, “scientific knowledge”, something that should not even be questioned or analyzed. It is enough to know that “Lviv”, “Poroshenko” and “the far-right” match perfectly. It is “normal”, “well-known”, “indisputable”. Everybody knows it.

The case illustrates the problem of unbiased, “Moscow-free”, coverage of Ukraine’s developments—too broad and complex to be covered here. It also sheds light, however, on a number of lesser issues, one of which I would like to specifically address: the inadequate understanding of Lviv and the region which are often unduly caricatured and sometimes— also unfairly—embellished and lionized.

A “Hotbed” of Nationalism

Lviv, with its population of about 750,000 people, is only the seventh-largest city in Ukraine. In the western part of the country, however, it is the largest one, at least three times bigger than any other city in the region. This endows Lviv informally with a certain metropolitan status—as the cultural, educational and, to a certain degree, economic and political center of seven oblasts, loosely subsumed under the rubric “Western Ukraine”. In fact, Western Ukraine consists of four very different historical regions (Halychyna / Galicia, Volyn, Bukovyna, and Transcarpatia),—quite distinct and, in some points, not particularly supportive of one other. The main common feature that unites them, apart from the location, is their history, in particular their relatively late—only during WWII—incorporation into the Soviet Union. This made them much less exposed to the crude Soviet policies of industrialization, collectivization, and Russification, although they were not fully exempt from that kind of social engineering.

The net result of these (and some other) historical developments was a lower level of Russification/ Sovietization, a lower loyalty to the regime and a more critical stance on the part of the inhabitants toward the official ideology and propagandistic clichés. They simply did not internalize the “Sovietness” to a degree achieved further east, and were more similar in this regard to inhabitants of Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia or the Baltic states. The most conspicuous feature, however, that made Western Ukraine strikingly different from the rest of the country and, more generally, from Soviet “normalcy” in the eyes of any visitor from the east, was the predominance or at least free use of Ukrainian in the urban environment.

In all other regions beyond the west, any use of Ukrainian in public was stigmatized as a sign of rural backwardness or, worse, a defiant manifestation of “Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism”. Western Ukrainian cities embodied the latter, in popular beliefs, legends and anecdotes, but also in all kinds of Soviet propaganda. The guerrilla resistance to the Soviets after WWII only strengthened the staunchly “nationalistic” image of the Western Ukrainian region, with the city of Lviv placed naturally at the very center of that myth.

The Russo-Ukrainian war and the ensuing civic mobilization have substantially changed the notion of “nationalism” in Ukraine. Back in 2005, only 27% of respondents in a nationwide poll saw it as an ideology that “aims primarily at the transformation of Ukraine into a strong state, with a high international reputation and decent level of citizen’s well-being”. As many as 41% assessed it negatively—as an ideology, that “splits society into ethnic Ukrainians and ‘non-Ukrainians’ and strives to restrict the rights of the latter group”. (14% defined nationalism neutrally, as a peculiar historical phenomenon that used to exist in Western Ukraine in the 1940s-1950s but which was passé today; 18% declined to respond). In 2015, the same pollsters11 found the opposite attitudes: 47% defined nationalism positively, as a useful transformative force, and only 24% held the earlier negative view. Remarkably, a positive view of “nationalism” prevailed, albeit minimally, even in Ukraine’s East (38.4 vs. 37.7) and Donbas (37.4 vs. 32.2).

The cliché is especially popular in the international media that refers recurrently to Ukraine’s “nationalistic West” as counter-opposed to the presumably “pro-Russian East”.

This did not impact, however, the general view of Western Ukraine, and Lviv in particular, as the hotbed of Ukrainian “nationalism”, as something exceptional,—not necessarily negative but still abnormal. The cliché is especially popular in the international media that refers recurrently to Ukraine’s “nationalistic West” as counter-opposed to the presumably “pro-Russian East”.12 In fact, the binary opposition is patently false insofar as the two key adjectives that make it, do not match one other. The true antonym to “nationalistic” should be either “internationalist” or “cosmopolitan”, but certainly not “pro-Russian” as it belongs to an apparently different semantic field. The proper antonym for it should be either “anti-Russian” or “pro-Ukrainian” (“pro-Western”, “pro-European”, etc.).

The false binary opposition is tricky because it manipulates not just semantics, but reality. It implies that being “pro-Russian” or else, Russian-speaking, absolves anybody from being “nationalistic”,13 while being “nationalistic” is a primordial and perhaps genetically determined feature of Ukraine’s West. The consequences of these mental short-cuts and semantic manipulations are dramatic since they facilitate many more distortions—as was briefly exemplified at the beginning of this article. Nationalism is too charged and ambiguous a word to be used arbitrarily, especially in reports about a country which most people know nothing about (or, worse, know something from poisonous sources such as RT and associates).

The primary goal of this essay is to, therefore, take a closer look at so-called “West Ukrainian” nationalism, its specific manifestations in the city of Lviv, its impact on people’s behavior and value systems and on their perception of other regions and self-perception within the country. I would draw on available sociological data which are quite rich but which come from different, often methodologically incompatible, surveys. In most cases, they cover the entire region of Western Ukraine, occasionally Galicia (Lviv, Ternopil and Ivano-Frankivsk oblasts), but very rarely Lviv itself. Some modest extrapolation of data is needed, therefore, so that the entire region (Galicia or the whole of Western Ukraine) serves as a rough sociological proxy for the city.

What is in the Data?

The everyday use of Ukrainian in public might be the most conspicuous sign of “nationalism” in the city of Lviv in the eyes of visitors from the east (either from Kiev, Minsk, or Moscow) but it certainly does not look like that in the eyes of the people who did not internalize Soviet “normalcy” which deemed any public conversation in Ukrainian (Belarusian, Moldovan, Kazakh, etc.) beyond a village, bazaar or Writers’ Union a deplorable deviation. Mass attachment to the native language is certainly not a unique Western Ukrainian feature, but is quite typical for most nations. The surveys demonstrate, that even in heavily Russified Eastern Ukraine, two-thirds of the respondents claimed Ukrainian as their “native language” and almost half of them speak it at home. Much fewer of them, however, dare to use it in public, this being a clear sign of an unfriendly social environment that still supports and reproduces discursively a supremacist colonial convention. Western Ukrainians did not internalize it, thus the region remains the only part of Ukraine where the number of urbanites speaking Ukrainian at home and in public is the same.14

This might be a sign of “nationalism” since any resistance to the dominant (imperial, in this case) convention requires some sort of “nationalistic” mobilization. This is, however, a rather defensive “nationalism” aimed at protection of its national “normalcy” against the imperial normalcy imposed from the outside. It might look abnormal and deviant to Easterners who have internalized the imperial view of all things Ukrainian as inferior. It is essential, however, quite a normal reaction, rather typical for most nations exposed to an external, either real or sometimes imaginary, threat.

While the free use of Ukrainian in the public space is the most conspicuous feature that makes Lviv and other Western Ukrainian cities notably different from their Eastern Ukrainian counterparts, there are many more dissimilarities, less obvious but statistically significant and variously exemplified by sociological surveys. Most of them are not necessarily proof of “nationalism” but certainly proof of a stronger national identity and higher concern with identity-related issues.

For instance, as many as 86% of ‘westerners’ declare themselves “patriots of Ukraine”, according to a recent opinion poll, while the national average is 83%15. By the same token, 89% of the respondents in Western Ukraine declare support for national independence (while Ukraine’s average is 71%, with 20% undecided);16 65% declare they are ready to defend their country with arms or in auxiliary as volunteers (the national average is 50%);17 72% identify themselves primarily as citizens of Ukraine (the national average is 65%);18 84% of respondents in the Lviv oblast feel proud to be citizens of Ukraine (the national average is 69%).19

The surveys demonstrate, that even in heavily Russified Eastern Ukraine, two-thirds of the respondents claimed Ukrainian as their “native language” and almost half of them speak it at home.

The apparently stronger national identity of the region also determines its stronger pro-Western (primarily pro-EU and pro-NATO) orientation,20 as well as support for a set of values deemed “European”— democracy,21 liberalism,22 free market23 and civic participation.24 The differences between the Western and Eastern regions are not that high, since all of them share a rather low East European civic/political culture and, to a different degree, legacies of Sovietism.

Nonetheless, they are statistically discernible and quite stable. The connection between identity (nationalism) and pro-Western orientation (set of values) is determined by a peculiar development of the Ukrainian national project since its very inception in the first half of the nineteenth century. The main challenge for Ukrainian nation-builders has been emancipation from the Russian empire that did not recognize Ukrainians as a separate nationality. This entailed an even more difficult task—mental emancipation from the imagined East Slavonic/Orthodox Christian community that stemmed symbolically from the Kievan Rus but was completely appropriated by Muscovy.

The West became for Ukrainians an alternative center to identify with and acquire the much-needed symbolic and discursive resources to withstand imperial dominance. The West represented modernity much more than Russia but also required the acceptance of western values, at least at the normative level. This made Ukrainians “Westernizers by default”: they either had to give up their nationalistic ambitions and dissolve in a greater Russian nation, or tame their nativist, deeply ingrained Slavic-Orthodox anti-Westernism and adopt (unpalatable sometimes) Western cultural and political patterns.25

The other interesting manifestation of the stronger national identity in Western Ukraine is a higher level of optimism expressed by the inhabitants of the region. As many as 87% of Westerners believe that Ukraine could overcome all problems and challenges (Ukraine’s average is 81%); 63% of Westerners believe Ukraine is developing in the right direction (16% claim the opposite, while the national average is 51% vs. 23%); 42% of Westerners believe there were more positive things than negative since independence (10% claim the opposite, while the Ukrainian average is 26% vs. 23%); 39% of Westerners look to the future with optimism and 57% with hope (Ukraine’s average is 36% and 56% respectively);26 78% of respondents in the Lviv oblast view themselves as happy or relatively happy people (Ukraine’s average is 70%, with the highest results, again, in the west).27

Although Western Ukraine is the poorest part of the country (in terms of average salaries, personal income, and regional GDP per capita),28 most respondents consider themselves “middle class”, and assess the financial situation of their families much better than respondents in other oblasts. In the city of Lviv, only 6% of respondents claim that they do not have enough money for food, and only 14% contend that they can barely afford anything besides the most basic stuff (both figures are among the lowest in Ukraine).

Three-quarters of the inhabitants of Lviv (75%—the highest number in Ukraine) fall into the middle-income category: they claim they have enough money for food, clothes, shoes and other basic expenditures but need to save or borrow money for purchasing more expensive things. The upper-income categories (people who can afford everything or almost everything) are statistically insignificant in Ukraine, and fluctuate everywhere, including Lviv, around 4%. Neither income from the shadow economy nor remittances from abroad can explain this paradox persuasively enough, especially if we take into account the respective data from Kiev (64%)—a city which is much better-off, with the average salaries almost three times higher than in Lviv.29

As in the case of the higher social optimism, the patriotic mobilization might be the main reason for an apparently exaggerated assessment of personal well-being in Lviv and elsewhere in Western Ukraine—more or less in line with the sarcastic remark of the popular Lviv artist Volodymyr Kostyrko: “Before 1991, Galicians had poignantly felt two things— poverty and Russification. Now, they feel three things, happily—poverty, Russification and great joy from national independence”.30

All the examined data do not say much about the stronger “nationalism” of Western Ukraine but rather confirm the higher level of patriotism of Ukrainian-speaking Ukrainians who make up the absolute majority in the region. In ethnic terms, Ukrainians make up 95% of the population of Western Ukraine (in Donbas they make up only 69%, and 89% in the South and East); in linguistic terms, 93% claim Ukrainian as their native language while the national average is only 60% (84% in the Center, 42% in the South, 36% in the East, and 27% in Donbas).31 The city of Lviv has the same ethnolinguistic composition as the entire region: 97% of respondents declare themselves “ethnically Ukrainian”, 3% ethnically Russian; 89% speak Ukrainian at home, 4% speak Russian, 6% speak reportedly both languages.32

In other words, the eastern regions look a bit less “patriotic” just because they have a higher number of ethnic Russians and Russophones. This is not to say they are hostile or completely alien vis-à-vis Ukraine but they are much more likely, for obvious reasons, to have mixed cultural and, sometimes, political loyalties vis-à-vis Russia as a kin state. This, in turn, increases the probability of a lower attachment toward all things Ukrainian and of a more ambivalent and hesitant stance on certain sensitive political issues.

Different Kinds of ‘Otherness’

To decouple patriotism from nationalism is not an easy task until and unless the latter takes an aggressive stance against local minorities and/or outside groups or nations. In all other terms like strength or salience of national identity or its supremacy over other identities the person possesses, they are virtually indistinguishable.

One of the possible ways to determine potentially dangerous features of local nationalism is to measure the level of xenophobia.

As in the case of the higher social optimism, the patriotic mobilization might be the main reason for an apparently exaggerated assessment of personal well-being in Lviv and elsewhere in Western Ukraine.

In this regard, the nationwide surveys carried out by the Kiev International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) do not bode well for Western Ukrainians. The region was scored with 4.7 on the Bogardus seven-point scale, while the national average appeared to be 4.2 and the lowest score of 3.6 was found in Ukraine’s South.33 Lviv, in fact, might be closer to the 4.2 average than to the 4.7 regional extreme because cities are usually more tolerant than rural areas.

One should also probably keep in mind that the aggregate data contains the findings from a very peculiar region of Transcarpatia where the largest part of Ukraine’s heavily stigmatized Roma minority is concentrated. This also inflates the aggregate regional data, although Lviv may have little to do with the problem. Nonetheless, the obtained results barely characterize the region as proudly “European”.

The Razumkov Center research seems to confirm the KIIS results, although it employs a different measurement.34 The pollsters asked the respondents to list the members of an ethnic group that he/she would like to have as a neighbor and, separately, to list those whom he or she would not like to have nearby. Again, the Western Ukrainians appeared to be the least tolerant, with only 39% claiming that the ethnicity of the neighbors does not matter (the national average was 53%), while 44% of the Westerners expressed their preference for an ethnically Ukrainian neighborhood (the national average was 29%).

Among the least desirable neighbors, Roma predictably took the lead, with the highest negative result of 41% scored in the West (the nationwide average was 32%). Russians came in second, seen negatively by 30% of the Western Ukrainians (the national average was 13%). While the negative othering of Roma is a typical phenomenon for all of Central and Eastern Europe, specifically for the areas where Roma are concentrated (65% of respondents in Czech Republic and in Slovakia would not like to have Roma as neighbors, the same negative attitude is expressed by 67% of respondents in Bulgaria, 55% in Belarus, 51% in Russia, 42% in Slovenia,35 62% in Ital36y), the pronouncedly negative attitude towards Russians is a relatively new phenomenon, that indicates instead the strong disapproval of the politics of the Russian state rather than a genuine ethnic bias.37

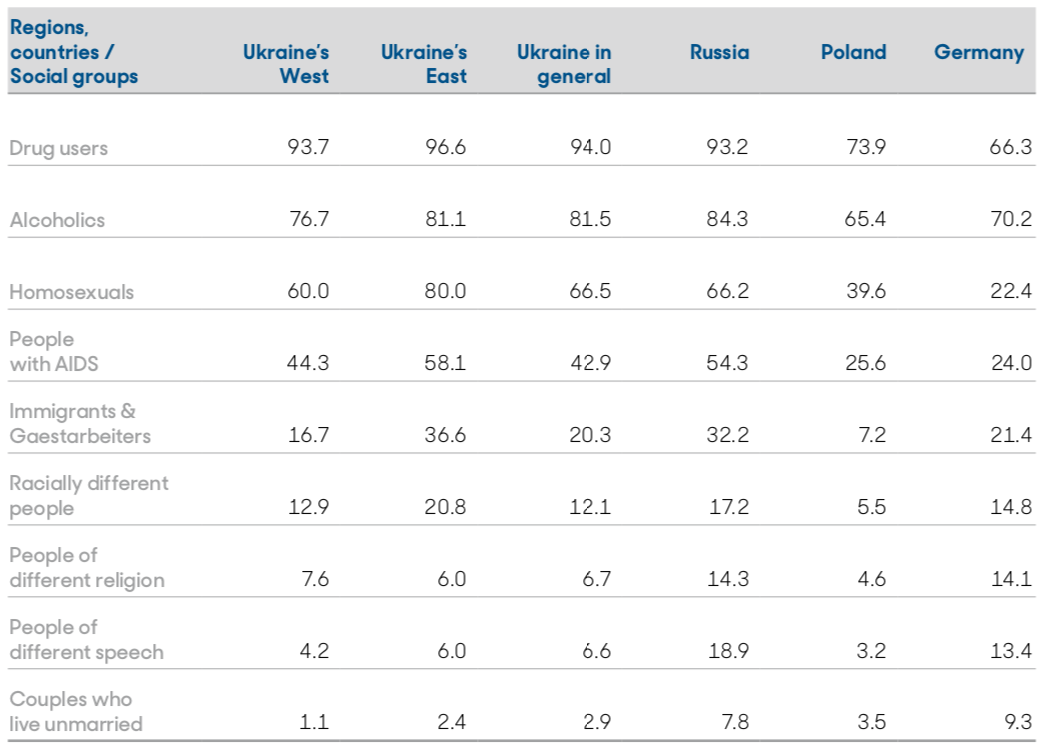

Which groups of people would you not like to have as neighbors?

TABLE 1: Regional and nationwide responses to the question “Which groups of people you would not like to have as neighbors?” (the respondents could choose from the list any number of answers)

As to the other minorities, Western Ukrainians are slightly more than the Easterners, inclined to place them on the negative list as undesirable neighbors, but also, paradoxically, more willing to place them on the positive list of preferable neighbors (e.g., 4% of the Westerners would not like to have Poles as their neighbors but 28% would like them, while the national average is respectively 3% and 18%).38 The paradox probably stems from the fact that minorities are concentrated primarily in the West and are much more conspicuous and ethnically marked there than in the East. This probably makes Westerners’ attitudes toward minorities more concrete, based on personal experience and therefore differentiated. They might be more positive or more negative but, in any case, less indifferent.

In the East, the minorities are pure abstractions, ethnic only by name. In most cases, they are heavily Russified and virtually indistinguishable from the Russian-speaking majority. One may only guess what the Easterners’ attitude toward ethnic neighbors would be if they were really different, beyond the tenets of Soviet “internationalism”. The empirical evidence from Ukraine’s south-east does not characterize local Russophone urbanites very positively. In a number of cases, they express unprovoked (and unmatched in the West) aggression against at least two groups that became increasingly visible in the post-Soviet period—Tatars in Crimea and Ukrainian-speakers in Odessa, Kharkiv, Dnipro and other large cities.39

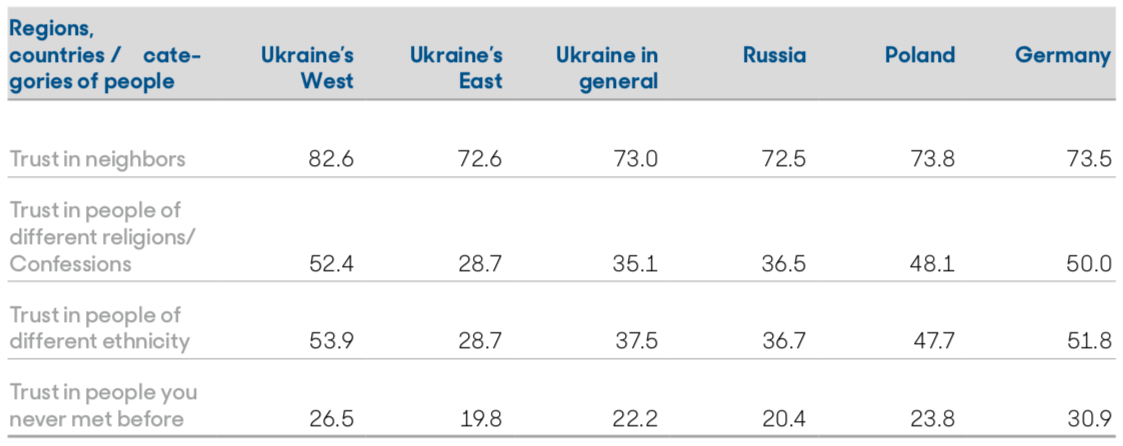

How much could you trust the following categories of people?

TABLE 2: Regional and nationwide responses to the question “Which groups of people you would not like to have as neighbors?” (the respondents could choose from the list any number of answers)

The subsequent study by the Razumkov Center sheds more light on the issue of regional tolerance by extending the list of (hypothetical) “undesirable neighbors” and also attaching, for comparison, the responses from a few other countries. Remarkably, in all but one minor issue (of religion) Western Ukrainians appeared to be more tolerant than their compatriots from the East and, in most cases, than the respondents from Russia.40

The same study also provides remarkable data on social trust: in Ukraine, in its regions, and in a few neighboring countries.41 Here, once again, Western Ukrainians appear to be a bit closer in their attitudes to Poles and Germans than to their Eastern brethren and Russians. While the trust in neighbors or completely unknown strangers probably indicates the level of social capital only, the trust in people of other religions/confessions or other ethnicity/nationality also indicates some level of ethnic/religious biases (or lack thereof ).

The Razumkov Center data does not disprove the KIIS findings that indicate a rather high social distance of Western Ukrainians from other ethnic groups along the Bogardus scale. It does, however, place into doubt the presumably lower (as the KIIS study contends) distance of Eastern Ukrainians vis-à-vis the same groups. It actually indicates a substantially higher bias vis-à-vis real otherness in the East than in the West.

The most probable explanation of the data discrepancy is that the KIIS study assumed the same notions of ethnicity in both the West and the East while in fact, they were quite different. In the West, “ethnicity” seems to be more meaningful, more culturally significant than in the East, where it used to be a sheer declaration, enshrined in the Soviet documents but void of any significant (non-Soviet/non-Russian) cultural markers. It largely reflects the legacy of Soviet “internationalism”: ethnicity does not matter—as long as the person is “ours”, i.e. Soviet and Russian-speaking.

This notion of “otherness” (and “our-ness”) is reflected in a peculiar way in one more nationwide survey carried out in 2006 by the Razumkov Center that asked respondents “How are inhabitants of Ukraine’s different regions and of some neighboring countries close to you in character, habits and traditions?”

Predictably, Kiev and Central Ukraine were defined as closest to everybody, while Turkey, Hungary and Romania were named as the furthest.42 Remarkably, Western Ukraine was placed not only behind Russia but also behind Belarus—a country virtually unknown in Ukraine, with very limited personal contacts between the citizens. It was recognized as “close” probably only because of a deeply internalized Soviet myth about the tripartite East Slavonic “brotherhood” that also adds Belarus to the Russo-Ukrainian duo.

To decouple patriotism from nationalism is not an easy task until and unless the latter takes an aggressive stance against local minorities and/or outside groups or nations.

The 2016 survey offered a similar question (“How close to each other are the inhabitants of different regions in their cultures, traditions and views?”) but applied a different scale of measurement that made the results of the two surveys difficult to compare. What is clear, however, from juxtaposition, is that the Western Ukrainians are still perceived as more distant from the Eastern Ukrainians than, generally, the citizens of Ukraine from the citizens of Russia. And, in a new twist in the public mood, the inhabitants of Galicia are seen as more distant from the inhabitants of Donbas than are the citizens of Ukraine in general distant from the citizens of the EU.43

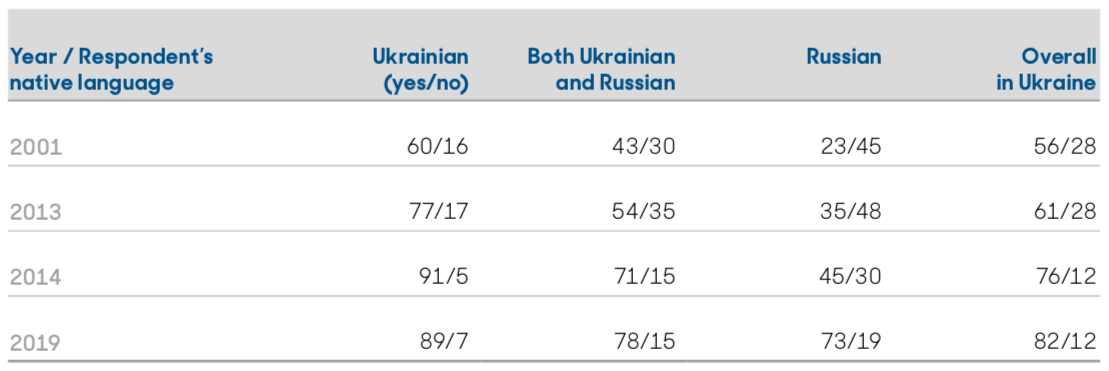

If you had to choose now, would you support the declaration of Ukraine’s independence?

TABLE 3: Support for national independence from Ukraine’s major ethnolinguistic groups as indicated by their answer to the question “If you had to choose now, would you support the declaration of Ukraine’s independence?” (only ‘yes’ and ‘no’ answers are shown in the table).

This does not necessarily mean that the inhabitants of Galicia or Western Ukraine are considered “worse”, or “hostile”. Actually, the 2015 nationwide survey represented a rather positive image of Western Ukrainians, seen by their co-citizens. They defined them primarily as “patriotic” (38%), “religious” (35%), “cultured” (28%), “committed to family values” (23%), “clever and educated” (16%), and “ready to help” (14.5%).

The negative views gained much lower currency (the respondents could mention up to three features). 6% of respondents defined Galicians as “cunning”, 5% as “aggressive”, 5% as “uncultured, uneducated”, and 2% as “lawless”.44 There is no earlier data, unfortunately, to trace the dynamic of changes but they seem to be coterminous with the spread of a positive meaning of “nationalism”. Nonetheless, a feeling of otherness seems to prevail: Galicians might be OK but not “like us”. They fall out of the mythical matrix of the East Slavonic/Orthodox Christian imagined community.45

At the Bottom-line

All the apparent differences between Ukraine’s regions and ethno-linguistic groups notwithstanding, they are gradually evolving in the same— pro-Ukrainian and pro-Western—direction, in term of their identities and political attitudes. This largely explains why Ukraine did not split under external pressure—as was expected in Moscow and as often happens with truly divided societies. The ethnolinguistic groups in Ukraine differ only in terms of the different levels (intensity and unanimity) of their loyalty toward Ukraine, but not by opposite loyalties toward different states.

The same dynamics can be also observed in different age groups: the younger the people, the more likely they are to be strongly pro-Western and pro-Ukrainian. All this seriously places in doubt the “exceptional” and “abnormal” status of Western Ukraine. The social dynamics instead implies a gradual “normalization” of the entire country, although painstaking, contradictory and convoluted. In any case, the higher level of patriotism and strong, preeminent and salient national identity in Western Ukraine cannot be seen as proof of “nationalism” (in negative terms)—as long as they do not clearly match with xenophobia and ethnic exclusiveness.

Western Ukrainians are not as tolerant as we would like them to be, but their attitude toward all kinds of otherness (not only ethnic but also confessional, gender, or social) does not differ substantially from their compatriots to the east or neighbors to the west. Their support for far-right parties and candidates is lower than in most European nations and, actually, lower than in Eastern Ukraine—if we consider the mass support for “Opposition Platform” (the former Party of Regions) at least partially as an expression of Putin-style Russian nationalism.

Western Ukrainians are slightly more than the Easterners, inclined to place them on the negative list as undesirable neighbors, but also, paradoxically, more willing to place them on the positive list.

Finally, the proverbial Western Ukrainian “nationalism” has a rather inclusive view of the Ukrainian nation. Only 16% of respondents in the West define it in ethnic terms—as people of Ukrainian origin, regardless of where they live. Paradoxically, in Eastern Ukraine this view is shared by a substantially higher number (24%) of respondents. Both in the West (50%) and the East (52%), the majority opt for a civic definition of the Ukrainian nation—by citizenship.47

The only parameter in which the Westerners are more exclusive is native language. 28% of them contend that ethnicity does not matter but that command of Ukrainian is a must. In the East, the figure is lower, at 17%. Once again, the underlying desire in this attitude is probably not so much to exclude the “others”, but rather to include them by encouraging them to learn and use Ukrainian—the language that still is discursively stigmatized and marginalized in most urban centers of Ukraine.

Western Ukrainians are still perceived as more distant from the Eastern Ukrainians than, generally, the citizens of Ukraine from the citizens of Russia.

Western Ukrainians in general and the citizens of Lviv in particular face a difficult dual task: to tackle their burdensome “nationalist” image and play the self-assigned role of the Ukrainian “Piedmont” that leads both the national revival and social modernization. The emphasis on the latter might be a good key to the successful managing of the former.

- news.vice.com/en_us/article/qvy7vx/heavyweights-from-the-white-nationalist-world-will-be-bonding-in-finland-this-weekend-heres-what-they-want

- westnews.info/news/U-Lvovi-Nacionalnij-Korpus-gotuyetsya-jti-do-Poroshenka.html

- gordonua.com/ukr/news/politics/u-vinnitsi-vidbulisja-zitknennja-politsiji-z-natsionalnimi-druzhinami-842447.html

- gordonua.com/ukr/news/localnews/pered-zustrichchju-poroshenka-z-zhiteljami-ivano-frankivska-vidbulisja-sutichki-z-uchastju-natskorpusa-i-natsdruzhin-u-politsiji-povidomili-shcho-postrazhdalih-nemaje-822218.html

- glavcom.ua/news/nacionalisti-z-nackorpusu-zyavilisya-na-mitingu-poroshenka-u-cherkasah-575854.html

- gordonua.com/ukr/news/politics/de-vidrubani-ruki-natskorpus-vlashtuvav-aktsiju-pid-chas-vizitu-poroshenka-v-chernigiv-807361.html

- zik.ua/news/2019/03/16/pid_chas_peredvyborchogo_ mityngu_poroshenka_v_ poltavi_natsdruzhyny_ vlashtuvaly_1530665

- hromadske.radio/news/2019/03/11/predstavnyky-nackorpusu-pryyshly-na-vystup-poroshenka-u-zhytomyri

- gordonua.com/ukr/news/politics/biletskij-na-mitingi-poroshenko-mi-prihodimo-zapitati-u-nogo-shcho-z-svinarchukami-shcho-zi-skotami-jaki-v-normalnij-krajini-sili-b-dovichno-8478-48.html

- www.Kievpost.com/multimedia/photo/national-corps-rally-demand-arrest-of-alleged-corruption-suspects-photos

- razumkov.org.ua/uploads/journal/ukr/NSD161-162_2016_ukr.pdf

- E.g., “Dnipropetrovsk stands on the fault line between the pro-Russian

east of the country and anti-Russian, nationalistic west” (Olga Rudenko, In

East Ukraine, fear of Putin, anger at Kiev. USA Today, 14 March 2014, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2014/03/14/ukraine-crimea-referendum/6319183). “There is a genuine divide in Ukraine between a nationalist-dominated west and a Russian-speaking east” (Dovid Katz, The Hushed-Up Hitler Factor in Ukraine. Portside, August 2014, https://portside.org/2014-08-21/hushed-hitler-factor-ukraine-and-neo-nazi-brigade-fighting-pro-russian-separatists); “The pro-European outlook that fits so easily in the country’s west, where Ukrainians are nationalists, angers the ethnic Russians who people the industrial east” (Mara Bellaby, Ukraine Soccer United Divided Nation. Associated Press, 28 June 2006). - A modified form of the same cliché absolves all Russian-speakers from being “nationalists”, while equating implicitly “nationalism” with speaking Ukrainian: “Zelensky’s presidency could reduce the country’s historical fission between nationalist west and Russian speaking east”. (Asia Times, 5 April 2019, https://www.asiatimes.com/2019/04/article/moscow-left-friendless-in-ukrainian-presidential-race/). Or: “For years, the story of Ukrainian elections was divided between the Ukrainian-speaking and nationalist west of the country, and the Russian-speaking south and east”. (Thomas de Waal, What Is at Stake in Ukraine’s Election? Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 21 March 2019; https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/03/21/what-is-at-stake-in-ukraine-s-election-pub-78659).

- razumkov.org.ua/uploads/journal/ukr/NSD169-170_2017_ukr.pdf

- ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/rg_patriotyzm_082019.pdf

- dif.org.ua/article/gromadska-dumka-ukrainina-28-rotsi-nezalezhnosti-derzhavi

- www.razumkov.org.ua/upload/Identi-2016.pdf

- ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/rg_patriotyzm_082019.pdf

- ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/rg_40000_portraits_of_the_regions_122018_press.pdf

- ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/rg_40000_portraits_of_the_regions_122018_press.pdf

- When asked to choose between a “democratic system of government or prosperous economy”, 54% of respondents in Lviv mentioned democracy as more important, while 31% bet on economy. This is the highest level of support for democracy in Ukraine. Generally, all West Ukrainian cities occupy the upper part of this rating, while the South-eastern cities are mostly at the bottom. https://www.iri.org/sites/default/files/2018-3-22_ukraine_poll.pdf A few months earlier, in a similar survey, 67% of respondents in Western Ukraine defined democracy as the most desirable political system for the country (the national average was 56%).http://razumkov.org.ua/uploads/socio/2017_ Politychna_kultura.pdfIn 2015, at the height of military activity in Donbas, 56% of respondents in Western Ukraine still defined democracy as the most desirable political system for the country (the national average at the time was 51%). http://www.razumkov.org.ua/upload/Identi-2016.pdf

- Liberalism is not a very popular ideology in Ukraine (as elsewhere in Eastern Europe): less than 3% support it in both West and East. But there are twice as many supporters of “national democratic” ideology in the West (28%) than in the East (14%), while the support for overtly illiberal ideologies is roughly the same: 4.7% for radical nationalists and 0.4% for communists in the West, and 2.3% for radical nationalists and 2.1% for communists in the East. http://razumkov.org.ua/napriamky/sotsiologichni-doslidzhennia/presreliz-tsentru-razumkova-ideolohichni-oriientatsii-hromadian-ukrainy.West Ukrainians express much stronger support for unrestrained freedom of speech – against all forms of censorship (64% versus 13%); while the national average is 42% vs. 26%. http://ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/rg_orientyry_052013.pdf

- ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/rg_orientyry_052013.pdf

- West Ukrainians demonstrate, as a rule, the highest turnout in all national elections. They also express the highest readiness for all forms of protest (46% versus the national average of 37%) in case their rights and interests are infringed by authorities.http://ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/rg_electoral_052017_press.pdf. Also, importantly, 43% of Westerners agree that their personal engagement is needed to change the situation in the country for the better, 39% disagree. The nationwide attitude is the opposite: only 33% of respondents agree, 47% disagree. http://razumkov.org.ua/uploads/socio/2017_Politychna_kultura.pdf.

- doi.org/10.2307/3650067

- dif.org.ua/article/gromadska-dumka-ukraini-na-28-rotsi-nezalezhnosti-derzhavi

- ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/rg_40000_portraits_of_the_ regions_122018_press.pdf

- csrv2.ukrstat.gov.ua/operativ/operativ2008/gdn/dvn_ric/dvn_ric_u/ dn_reg2013_u.html

- www.iri.org/sites/default/ files/2018-3-22_ukraine_poll.pdfOne more explanatory factor may be the structure of the West Ukrainian economy where small and medium-size businesses prevail. This ensures a more equal distribution of income than the oligarchic economy that prevails in the East and enriches enormously a few at the cost of the many.https://www.economist.com/free-exchange/2016/01/20/the-ukrainian-economy-is-not-terrible-everywhere

- www.ji.lviv.ua/n23texts/kostyrko-146.htm

- razumkov.org.ua/uploads/journal/ukr/NSD169-170_2017_ukr.pdf

- www.iri.org/sites/default/files/2018-3-22_ukraine_poll.pdf

- kiis.com.ua/?lang=ukr&cat=reports&id=793&page=1

- http://www.razumkov.org.ua/upload/Identi-2016.pdf

- dbk.gesis.org/dbksearch/sdesc2.asp?no=7500

- europeanvaluesstudy.eu/2019/05/23/evs2017-results-from-a-survey-experiment-on-social-distance-in-italy/

- www.razumkov.org.ua/upload/Identi-2016.pdf

- www.razumkov.org.ua/upload/Identi-2016.pdf

- The 2011 Odesa case gained perhaps the broadest publicity because the Ukrainian-speaker was insulted by the state servant who, according to the 1989 law (never observed though), was obliged to know and use Ukrainian. See: Odesa Policeman Calls Ukrainian “Cow” Language, RFE/RL Newsline, 26 January 2011, http://www.rferl.org/content/ukrainian_language_cow/2288383.html.In private services, such situations are much more ubiquitous. One of the latest stories comes from the TV presenter Yanina Sokolova who approached conveniently an Odesa taxi driver in Ukrainian and received a boorish response: “You, fascist! We’ll take on you soon!” (Sokolova got into a scandal with a Ukrainophobic taxi-driver in Odesa. Obozrevatel, 22 July 2019, https://www.obozrevatel.com/society/sho-fshistyi-sokolova-popala-v-skandal-s-taksistom-ukrainofobom-v-odesse.htm). I discussed the problem in more detail in the article Ukrainian Culture after Communism: Between Post-Colonial Liberation and Neo-Colonial Subjugation, in: Dobrota Pucherova and Robert Gafrik (eds.), Postcolonial East-Central Europe: Essays on Literature and Culture (Amsterdam: Rodopi Publ., 2015), specifically p. 346-354.

- razumkov.org.ua/uploads/journal/ukr/NSD169-170_2017_ukr.pdf

- razumkov.org.ua/uploads/journal/ukr/NSD169-170_2017_ukr.pdf

- razumkov.org.ua/uploads/journal/ukr/NSD79_2006_ukr.pdf

- razumkov.org.ua/uploads/journal/ukr/NSD161-162_2016_ukr.pdf

- icps.com.ua/assets/uploads/files/national_dialogue/poll_for_regions/00_ survey_ukraine_ua.pdf

- www.eurozine.com/emancipation-from-the-east-slavonic-ummah/

- Dynamic of the patriotic views. Rating Sociological Group, August 2013, p. 12; http://ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/rg_patriotyzm_082013.2.pdf; Dynamic of the patriotic views. Rating Sociological Group, August 2014, p. 13; http://ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/rg_patriotyzm_082014.pdf; and Dynamic 2019, p. 8; http://ratinggroup.ua/files/ratinggroup/reg_files/rg_patriotyzm_082019.pdf.

- www.razumkov.org.ua/upload/Identi-2016.pdf