The EU needs improvement in its competitiveness and innovation performance. This cannot be achieved, however, without addressing the problems of regional and country differences.

The European Union is lagging behind its major competitors in terms of innovativeness and competitiveness in spite of the fact that in March 2000 the EU heads of state and governments launched the so-called ‘Lisbon Strategy’ with the aim of making Europe “the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world, capable of sustainable economic growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion.”

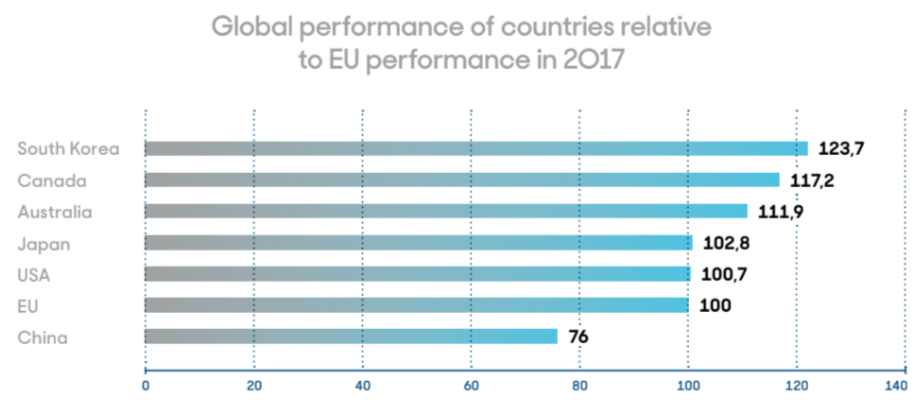

FIG 1: Source: The innovation potential of the EU Budget 2010–2027. Clingendael. January 2019.

As Figure 1 indicates, based on four groups of indicators taken from the European Innovation Scoreboard (2018), the so-called innovation potential of the EU is now the sixth among the key economic competitors in the world. As far as competitiveness is concerned, there are no EU member states among the first five countries on the IMD 2019 world competitiveness list. There are also no EU member countries among the first six countries in the 2019 World Economic Forum (WEF) list. The seventh is Germany.

Considering the deteriorating competitiveness position of the EU, it is understandable that the new EU leadership again emphasizes the importance of improving the innovative and competitiveness position of the EU.

Large Regional Differences

If we look at regional differences within the EU, we will find that they are considerably large.

On the IMD list, 15 years after enlargement, Slovakia is in the 53rd position out of 62 evaluated countries. Hungar y is 47th, Poland is 38th and only the Czech Republic has a better, 33rd position.

On the WEF list, which contains 141 countries, Hungary is 47th, Slovakia is 42nd, Poland 37th and the Czech Republic, again is in a slightly better, 32nd position. The differences within the EU are also demonstrated on the EU Innovation Scoreboard 2019, on which, among the 28 countries the Czech Republic is 14th, Slovakia is only 22nd, Hungary 23rd and Poland 25th.

Considering the deteriorating competitiveness position of the EU, it is understandable that the new EU leadership again emphasizes the importance of improving the innovative and competitiveness position of the EU, and is determined to allocate more resources to achieve these objectives. There is no discussion, however, about how this shift can be achieved without decreasing the great differences among member countries.

The two key conclusions can be that a more balanced regional development is required to improve the general competitiveness and innovativeness of the EU and in achieving this corporations should play a decisive role.

The WEF1 warns the EU the following way:

— There is a sense of urgency and scale to undertake the necessary investments and implement the necessary reforms to boost competitiveness and avoid a lost decade for Europe.

— A competitiveness divide exists in the EU. The likely result will be a lack of sufficient economic and social convergence across member countries.

Ketels and Porter2 also point out the problems of regional differences, and—as one practical way to solve the problem—emphasize the importance of microeconomic and firm-level innovation.

They say: “The competitiveness priorities set at the EU level are right on average, but wrong for every individual European region and country. The central competitiveness challenge European countries and regions are facing is microeconomic: what is needed, is strengthening the fundamental drivers of firm-level productivity and innovation.”

The Differences Are Striking

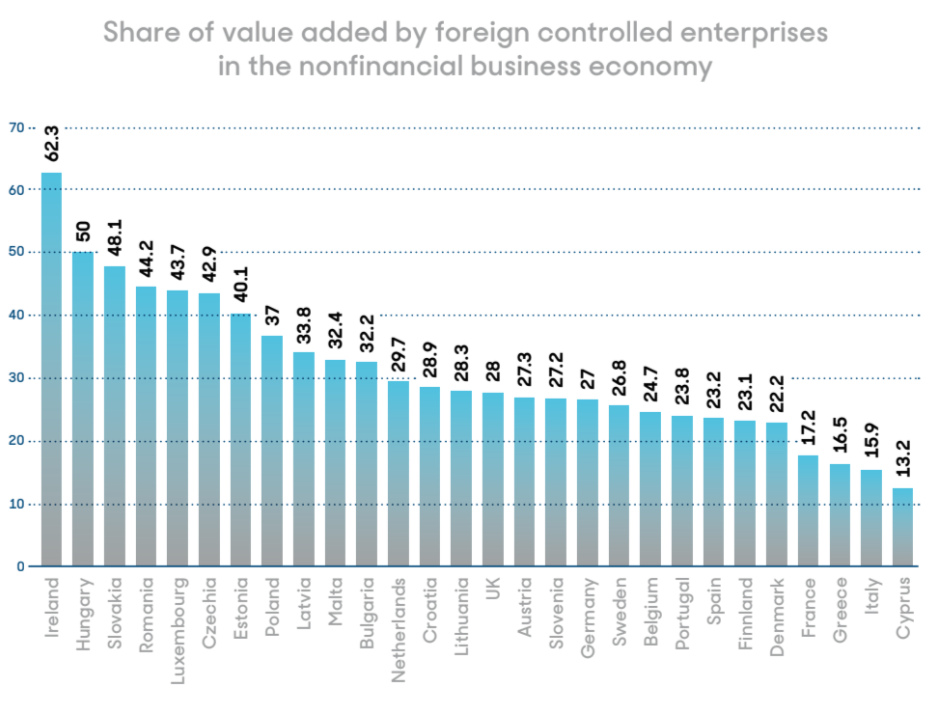

The two key conclusions can be that a more balanced regional development is required to improve the general competitiveness and innovativeness of the EU and in achieving this corporations should play a decisive role. Let’s see now how corporations perform in terms of innovativeness in the developed and less developed countries of the EU. It is especially important to analyze the performance of foreign-controlled businesses, as they—as can be seen in Figure 2.—, dominate the economies of the less developed countries in terms of value added. Value added is an important macro indicator, as it shows how much new value is created in an economy in a given time period.

FIG 2: 2017 (%). Source: Eurostat

Foreign-owned businesses—for statistical purposes called foreign affiliates—are considered to be enterprises resident in one country which are controlled by a unit resident in another. (Eurostat).

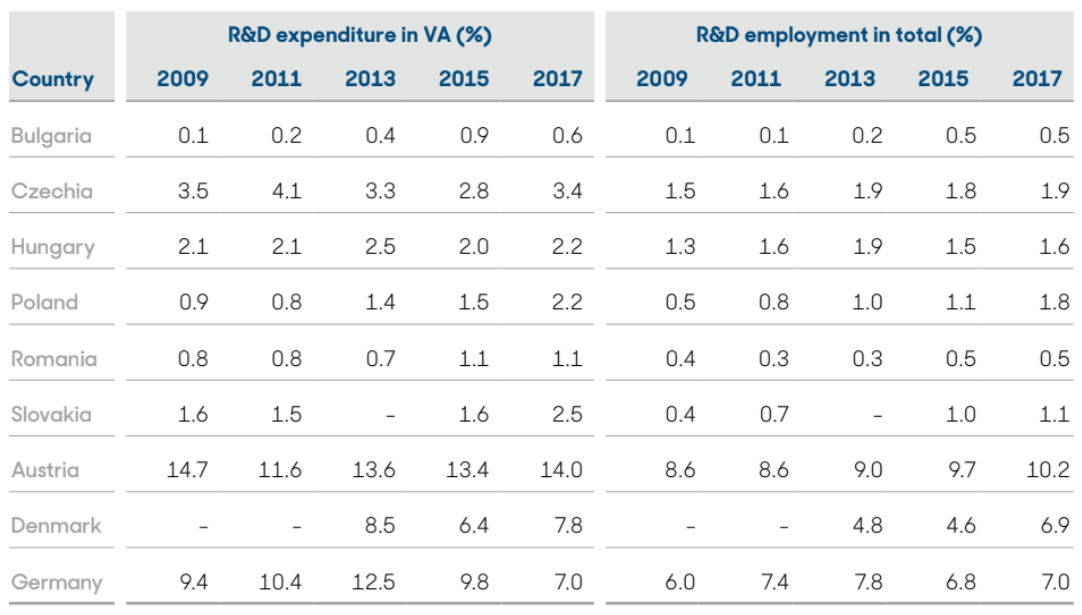

TABLE 1: Share of R&D expenditure in value-added (VA), and R&D employment in the number of persons employed in manufacturing in foreign-controlled enterprises (%). Source: Eurostat

A dominating value can be seen in Figure 2 added by foreign-controlled companies in the less developed countries, among them the V4 countries. This reinforces the argument that foreign-controlled companies could contribute to the innovative performance of these countries by investing in local innovation and knowledge creation.

The two most important indicators, measuring the innovative performance of businesses are the share of R&D expenditure in their value-added (VA), and their R&D employment as a percentage of the number of all persons employed. Table 1 demonstrates these numbers in 6 less developed and 3 developed countries in the most important economic sector, which dominates the industry in all these countries: manufacturing.

Although some data are missing, it is nevertheless evident that the differences between the developed and less developed countries are striking. The best-performing country from the less developed region is the Czech Republic, which is clearly mirrored in its innovation and competitiveness rankings. We could argue that this is obviously an indication that business innovativeness is a key for national innovativeness, and based on that for competitiveness, as well. R&D and innovation are also a key force behind productivity, which—in turn—leads to higher wages.

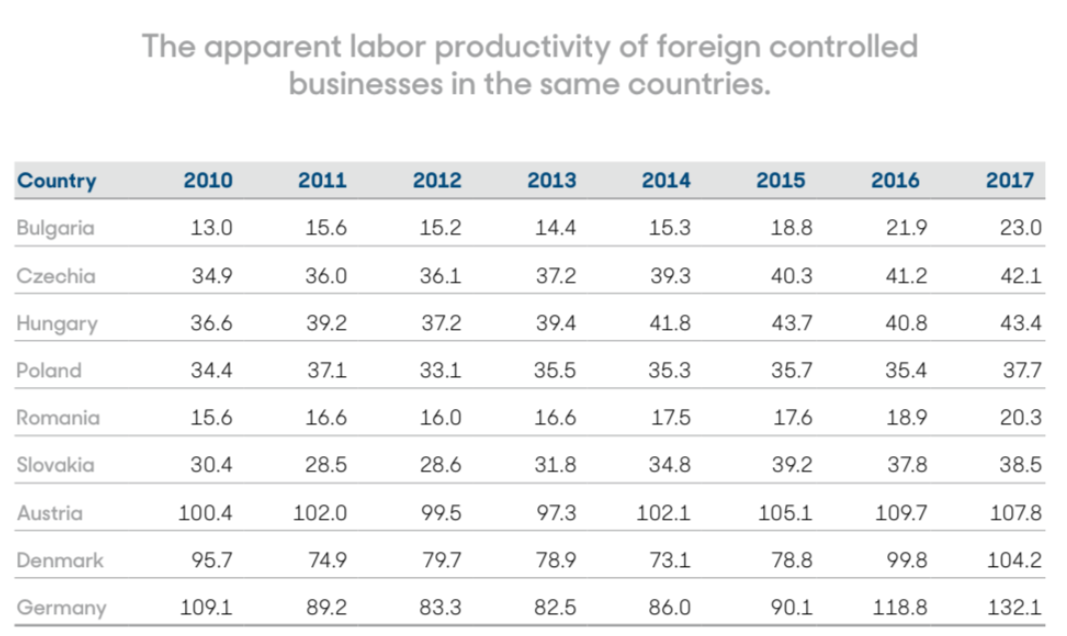

TABLE 2: Apparent labor productivity in foreign-controlled enterprises in manufacturing (thousand euro)

Apparent labor productivity measures value added per employee. It is a very objective and important indicator especially for those countries which are the homes of foreign value chains, because it clearly indicates the locally produced new value. This is also an important indicator from the local wage levels perspective, because wages are elements of value-added.

FIG 3: Year 2019. Source: Eurostat

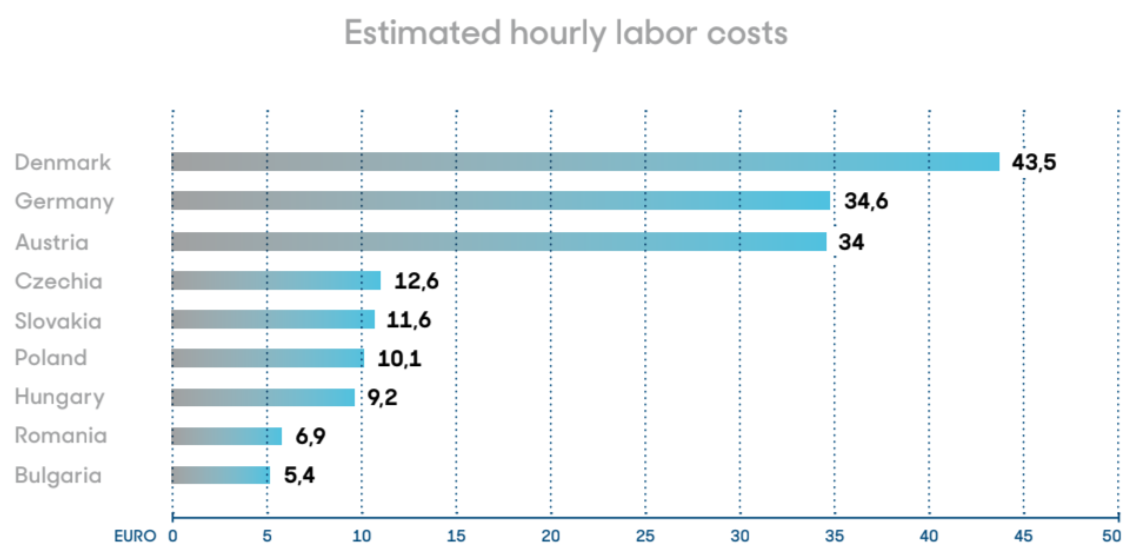

Table 2 indicates the tremendous differences among the more and less developed countries in terms of productivity which is strongly influenced by R&D investments and R&D employment. These numbers explain the fact that as the typical operations of foreign-controlled companies in manufacturing of the less developed countries are assembly operations which help optimize the costs of these companies, they can not contribute to improving competitiveness based on knowledge and innovation in the host countries. They also do not support social convergence in the EU, as keeping labor costs low means lower wages. This is demonstrated in Figure 3.

The EU is not only an Economic System

To sum up the arguments based on the facts, the EU indeed strongly needs improvement in its competitiveness and innovation performance. This cannot be achieved, however, without addressing the problems of regional and country differences. How can this be achieved when the business interests of the strong Western European companies is to minimize labor costs by locating the lowest value-added activities to the less developed ‘Eastern’ countries?

The Economist3 expressed this phenomenon the following way in 2011: “What is Germany’s secret? Germany has a cheaper-labor hinterland right on its doorstep in Central Europe that has helped companies raise efficiency and hold down pay.” It is obviously not only the German companies which are present in the manufacturing sector of the less developed countries, but they are definitely dominant in the key manufacturing sector: the production of motor vehicles and parts. Innovation is identified as a crucial driver of productivity, competitiveness and economic growth, as well as a key means of addressing societal challenges. Improving the competitiveness of strong Western companies by minimizing costs in their operations in the less developed countries will not help improve the competitiveness of the EU.

The EU is not only an economic, but also a social system. At least it should be. Therefore the economic and social future of the EU is strongly dependent on the success of the less developed countries. Otherwise, the entire system cannot be balanced and successful. The key question is then the following: how can the individual business interests, the cost optimizing drive of global value chains better serve the system-level success of the EU? How can this cost optimization drive be harmonized with the need for innovation-based economic and social convergence among all the EU member states? How could the capabilities of employees in the less developed countries be better utilized in better, more knowledge-based jobs for stronger local value-added creation and better living standards?

Improving the competitiveness of strong Western companies by minimizing costs in their operations in the less developed countries will not help improve the competitiveness of the EU.

These questions also should be investigated in the process of creating the new industrial and social policy and the new seven year EU budget.

- The Europe 2020 Competitiveness Report: Building a More Competitive Europe. 2012. World Economic Forum

- Ketels, Ch., Porter M.E: Towards a New Approach for Upgrading Europe’s Competitiveness. Working Paper 19-033. Harvard Business School. 2018.

- Germany’s Economy. Angela in Wunderland. 3 February 2011. The Economist